文:丁穎茵 博士(香港浸會大學視覺藝術院助理教授)

我是徹頭徹尾的考試懷疑論者。即使吃了老虎膽,誰敢給喬托(Giotto)、維拉斯奎茲(Velazquez),又或董源、石濤打分數?區區數字如何能夠計算藝術家經年累月對作品形式表現的知性與感性的思索?量化的評核又該如何衡度藝術家的想像力、修養及個性內涵所創造的藝術境界?難道馬蒂斯(Matisse)以色彩對比帶動畫面節奏的抽象構圖就不如布拉克(Braque)以幾何形式重構物象體積嚴謹?常玉以簡御繁的空靈又該如何與朱德群遒勁又跳脫的抽象語言作數值的比較?

by: Dr. Ting Wing Yan Vivian (Assistant Professor, Academy of Visual Arts, Hong Kong Baptist University)

I am absolutely skeptical about examinations. Who would have the nerve to grade the works by Giotto, Velazquez, Dong Yuan or Shi Tao? How can mere figures reveal the intellectual pursuits of an artist and sensual explorations in art-making throughout the years? How can quantitative assessments measure the quality of works of art created with one’s imagination and the depth of one’s inner self? Can one state that the voluptuous and coloured rhythm of Matisse in his compositions is less vigorous, compared to the geometric construction of form by Braque? How can the refreshing fluidity in the simple yet polished works of art of San Yu be compared with the energetic and rule-breaking abstract language by Chu Teh-Chun?

藝術的創造必先有「創」――跳脫常規的意念、手法,無中生有,才能有所「造」――將不著邊際的想像轉化成有意義、與人有共鳴的作品。然而,考試卻必須以齊一的標準給創造力劃下分數比重,評卷員又務必按章估算表現形式及學科知識的等級。這就如電腦遊戲將參與者按角色職業、性情、才能量化計算,將有血有肉有個性的人硬生生的搾壓成單向的數字。耐人尋味的是,遊戲的角色設定不值一哂,但考試制度的數值卻足以論斷人的資歷才性以至人生方向,豈不奇怪也哉?

這幾年,我在學院所遇見的考生更印證了考試懷疑論並非毫無道理。每當入學面試時,不少考生總是一股腦兒的訴說自己有多熱愛藝術,無奈為課業所迫難以抽時間看一看當前最重要的藝術展覽,甚至連本地藝術家也一無所知。當他們熱切的談論自己的作品,內容十不離九總是環繞自己的生活觀感、校園回憶,表達手法一如快餐的A、B、C 餐般貫徹始終。視覺藝術是發揮創造力、想像力與感知經驗的學科,創作過程講求探索與發現,作品是作者自我詰問的表現,也是與觀眾交流的平台。在這些千篇一律的視覺八股,我無法探知考生會否因接觸不同媒材的質感而興奮?又或從探索新主題以至找到新的表現方法而雀躍?反之,我看到的是工廠生產的製作,而非個人想像與表現的創造﹔感受到的是在考試制度掙扎求存的焦慮,而不見掌握藝術語言的喜悅與自信。究竟考試何為?

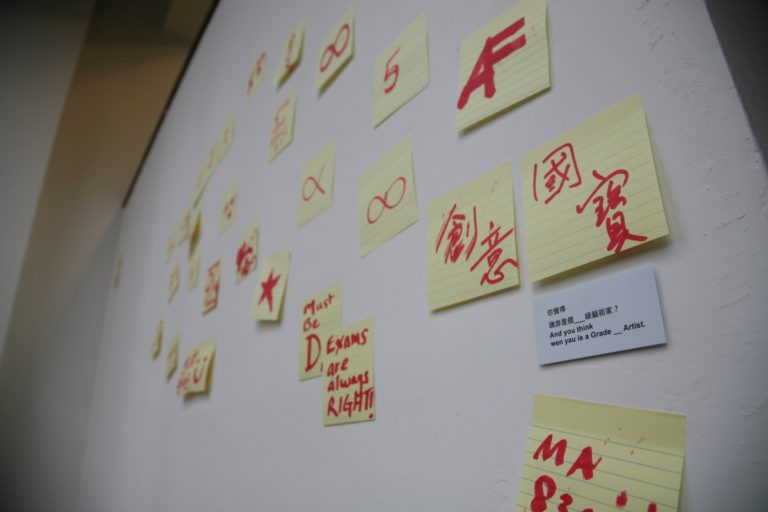

當不少考生為了分數而考試、又或為了實現當藝術家的夢想而考試,藝術家魂游卻以向制度挑機為由赴試。這兩、三年間,以藝術為職業、為知性追求的魂游竟然虔虔如高中生般製作應試作品集,又重拾畫筆跟老師學習素描、人體解剖等考試所規定作畫方式。魂游將應考視為藝術創作的延伸,藉由參與親身體驗所謂學習成效(learning outcomes)、考評規章(assessment criterion)的底蘊。作品所呈現的不僅是練習作品、作品集、考試成績,又或有關過程的紀錄,而是考試制度本身的問題:為什麼藝術家竟然淪為「丁級」考生?為什麼視覺藝術科包羅了傳統藝術形式、設計及工藝、新媒體等創作形式,但考試卻偏重以繪畫技巧斷定考生對視覺藝術的認識?為什麼考試所指定的「創作」形式竟然有固定的規章程序可依循?為什麼講求創意與想像的學科偏偏屈從於近乎毫無個性的訓練?為什麼考試將學生置身於忍受課程規範與藝術興趣的角力?為什麼、為什麼…連串的問題令觀者反思自己的學習經驗、詰問考試何為,並試圖尋找新的可能。

魂游認為考試是一門藝術。她將這門投評核方式所好、依循「遊戲規則」的藝術轉化成既費時失事、又吃力不討好的創作方式,投身公開試也就沾染了堂吉訶德的浪漫。一如堂吉訶德所堅持的騎士精神,魂游以忠於自己的方式參與公開試――遵從考試章程、依照老師指導學習繪畫,卻又掙扎於考試規範與個人表現方式之間,反思考試與創作的矛盾與視覺藝術的本義。她所堅持的是以自由自主的方式理解世界,並以藝術整頓生活的內容。即使考試制度並沒有讓藝術家從容適意的畫畫,魂游並不如堂吉訶德的執迷,反倒承認自己畫畫本事不濟,並以冷靜又輕鬆的方式展示自身所曾遭遇的迷惘與氣餒,令人直面考試制度的虛妄、數值等級的橫蠻。當《堂吉訶德》一書毀掉了當時陳腔濫調的騎士小說,魂游向公開試的挑機的火力在於她努力的投入考試,但制度卻似乎沒有空間接納這樣的考生。假若考試制度難以容許考生發揮創意,視覺藝術科還剩下什麼?

我並不相信考試制度的效能,但卻相信視覺藝術帶給人的不是藝術形式的技巧鍛練,而是創造新生活的想像。魂游向公開試挑機的行動正表明藝術的力量在乎透過反思與詰問與觀者一同整理我們對現況的理解,從而創造生命的內涵。魂游的戰書雖然衝著考試制度而來,卻也向著觀者問:面對你的生活課題,你又是怎樣的藝術家?畢竟,唯有勇於想、敢於做,才能沖破數字的迷思,打開屬於自己的想像空間,找到屬於自己的創意方式。

————————————————–

註: 香港考試局在F級(不合格)之下設U級,是為不予評級。鄙人乃考場逃兵—從未參與視覺藝術的公開試,按理評賞藝術作品的能力當屬U級。

I am absolutely skeptical about examinations. Who would have the nerve to grade the works by Giotto, Velazquez, Dong Yuan or Shi Tao? How can mere figures reveal the intellectual pursuits of an artist and sensual explorations in art-making throughout the years? How can quantitative assessments measure the quality of works of art created with one’s imagination and the depth of one’s inner self? Can one state that the voluptuous and coloured rhythm of Matisse in his compositions is less vigorous, compared to the geometric construction of form by Braque? How can the refreshing fluidity in the simple yet polished works of art of San Yu be compared with the energetic and rule-breaking abstract language by Chu Teh-Chun?

The creation of art must, first of all, consist of the act of ‘creating’, which involves groundbreaking concepts and practices, the pushing of boundaries in everyday life and making something out of nothing. Only with this attempt to create, can there exist the “making” of art that transforms various abstract images from the imagination into artworks that resonate with people. However, examination must provide a set of marking schemes to weigh creative ability. Exam markers must follow the grading criteria to assess the work of a candidate in expression and his/her academic knowledge. This is similar to computer games that rate a game player, according to the occupation, personality and abilities of his/her role. Computer games turn a living being into a set of numbers by annihilating the subjectivity of this being. What becomes puzzling is that, despite the insignificance of the roles in computer games, the digits from an exam system are actually significant enough to determine one’s capability and even the direction for one’s entire life. How ridiculous!

In the past few years, the candidates I have met at the Academy have proven my skepticism about examinations to be absolutely correct. During every university admission interview, many candidates have expressed their passion for art, but feel helpless that they could not find the time to visit any important art exhibits due to their heavy workloads at school. Some of them do not even have any knowledge about the local artists. The artworks that these candidates passionately present to me are usually about their life experiences and memories of their school lives, and usually made in similar routine styles, like meal set A, B and C found on fast food menus. Visual Arts is a subject that encourages creativity, imagination, and perception. The creative process requires investigation and discovery. Artworks reveal questions probed by art-makers and also serve as a platform for exchanges with viewers. Under the rigid rules of the Visual Arts examination, will candidates be excited toward the various art media and materials? Or stimulated by newly explored themes and art expressions? In contrast, what I see is mechanical production, without any personal imagination and expression in the art-making process. What I feel is the anxiety for survival within the exam system, but not the joy and confidence of grasping artistic language. So why exams?

While a number of candidates sit on exams for good grades or towards their dreams of becoming artists, artist wen yau sits on exams to challenge the system. In the recent two to three years, wen yau, who pursues art as her career and for knowledge, has been well disciplined like a high school student to develop her art portfolio for exams, and study drawing and painting techniques preferred by these exams, such as sketch drawing, human anatomy, etc. wen yau extends exam-taking into an art making process. By participating in examinations, she has obtained first-hand experience on learning outcomes and assessment criterions. Her work not only presents the exercises, portfolios, exam results, or documentations of the process, but also poses questions about the examination system: why would an artist become a Grade “D” candidate? Visual arts cover the traditional art forms, design, crafts, new media, etc., but why does the visual arts exam only emphasize on the painting techniques of candidates? Why are there continual regulations for art “creation”? Why would a subject that should embrace creativity and imagination subvert to technical training without individuality? Why would examinations situate students in a struggle between curriculum regulations and their interest in the arts? Why? Why…? These series of questions engage the audience into reflecting on their own learning experiences and their understanding about examinations, in the hope of searching for new possibilities.

To wen yau, exam-taking is an art. She transforms this art form, which involves complying with assessment criterions and following the “rules of the game”, into an arduous and inefficient art-making process. Her work of sitting in the public exams appears to be as romantic as the adventures of Don Quixote. With the chivalric spirit of Don Quixote, wen yau sits in the public exams in an honest manner: by following the rules and regulations, and studying painting with an art teacher, even though this whole process traps her into a struggle between the guidelines for examinations and forms of personal expression. Within this struggle, she re-examines the dilemma between examination and art-making, and rethinks about the meaning of the visual arts. However, she insists on autonomous freedom to understand the world, and uses art to re-approach the contents of life. The examination system does not allow artists to paint according to their free will. However, wen yau is not as stubborn as Don Quixote. She admits that her painting and drawing techniques are not good enough. At the same time, she calmly exhibits the helplessness and deflated feelings from her experience, in order to expose the preposterousness of the exam system and the ruthlessness of the assessment criterions. While “Don Quixote” completely destroyed the cliché of the chivalric novels in its time, the significant power of wen yau’s challenge to the public exams lie in the non-rewarding effort that she has seriously devoted to exams. If the examination system cannot allow creativity from the candidates, what else is left in the Visual Arts subject?

I do not believe in the effectiveness of the exam system. On the other hand, I do believe that the visual arts is not about the technical training of any particular art medium, but to provide new imaginative sources in life. wen yau’s actions that challenge the public exam system clearly reveals that the power of the arts lies in the reflective questioning process which invites the audience to both reorganize their understanding of the world and create the essence of life. wen yau is directly challenging the examination system, but, at the same time, she is also asking her audience: in face of the problems in everyday life, what kind of artist are you? After all, only if one dares to think and act, will one be able to break through the myth of figures, thus opening up new possibilities and exploring one’s own creative practice.

————————————————–

Remarks: The Hong Kong Examination Authority sets Grade U below Grade F (Fail), to indicate that it refuse to assess the candidate. Since I have never attended any Visual Arts public exam, my ability to critique and appreciate artworks should belong to Grade U.

This text is written by Dr Ting Wing Yan Vivian for the exhibition

This text is written by Dr Ting Wing Yan Vivian for the exhibition

我是丁級藝術家 I am a Grade D Artist