November 2016

Dear Mr Kwok Woon

How do you do? I take the liberty to write to you, not only because I have heard of your name for long, but also all of your friends told me that you were a generous, casual, friendly and approachable person. Their eyes are always sparkling when they talk about you. Someone says, without you, Macao art scene is missing something. Someone says, he wishes there were more people like you in Macao. Someone tells me that nobody dislikes you. Someone also says that you had a colourful life, and always used colour to confront challenges. All these stories I have heard make you alive to me; your artwork makes you a vivid person too. Mr Kwok, don’t you have a larger-than-life character that stays in everybody’s mind? Ten years after you passed away, I have had a chance to cross your path by collecting stories from your friends, as if picking up lots of colourful fragments scattered in different corners…

[閱讀中文版]

‘Rainbow at midnight: the reality of night is darkness. I strive for radiance of seven colours.’

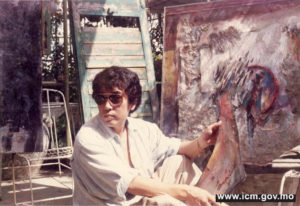

Your stories are always told with delight. I’ve heard that you moved to Hong Kong at the age of 23. You swore at the Lo Wu border that you would never get a job, never do business but to do art. Soon after establishing yourself as a painter in Hong Kong, you had an exhibition in Singapore where you met Joana Ling. You helped Joana to change a tyre for her vehicle on the road as a hero and she later on became your wife who accompanied and supported you all the time. I’ve also heard that you did wind-surfing and motor-racing, and I’ve seen your name on the list of Grand Prix entries. I’ve heard, too, that you drove around your red cabriolet and kept your large canvas at the back seats. Once you drove all the way from Hac Sa Beach to Ferry Terminal for only 7 minutes as promised. You also confidently hit the bee by rolling up a newspaper…

Moreover, I’ve heard that you had very broad interests and knowledge. Besides painting, you planted lots of exotic plants and vegetables in your rooftop studio. Other than art competition, you also participated in mahjong contest and even flower arrangement contest (in which you won the champion in your first entry). Despite your illness, you represented Macao in the First China-Zhoushan International Sand Sculpture Festival (1999) in Zhejiang right after radiotherapy – you were not specialized in sand sculpturing at all, but still diligently learned from others. I bet you were not feisty to join these contests or to angle for prestige and you insisted to keep your promise to participate. I recall the story of my father and his family, compelled by political changes, migrating from Guangzhou to Hong Kong many years ago. It was such a big challenge for them as a once-prestigious family to live under other’s roof in Hong Kong. Likewise, I understand how life had honed your fortitude in difficult times. To adhere to the ideal of art-making in a money-oriented society, one needs an adventurous spirit to sail against the current. As your wife, Joana, says, ‘nothing can baffle him!’ In old photos, I always find your bright eyes which mark your courage to meet challenges.

Moreover, I’ve heard that you had very broad interests and knowledge. Besides painting, you planted lots of exotic plants and vegetables in your rooftop studio. Other than art competition, you also participated in mahjong contest and even flower arrangement contest (in which you won the champion in your first entry). Despite your illness, you represented Macao in the First China-Zhoushan International Sand Sculpture Festival (1999) in Zhejiang right after radiotherapy – you were not specialized in sand sculpturing at all, but still diligently learned from others. I bet you were not feisty to join these contests or to angle for prestige and you insisted to keep your promise to participate. I recall the story of my father and his family, compelled by political changes, migrating from Guangzhou to Hong Kong many years ago. It was such a big challenge for them as a once-prestigious family to live under other’s roof in Hong Kong. Likewise, I understand how life had honed your fortitude in difficult times. To adhere to the ideal of art-making in a money-oriented society, one needs an adventurous spirit to sail against the current. As your wife, Joana, says, ‘nothing can baffle him!’ In old photos, I always find your bright eyes which mark your courage to meet challenges.

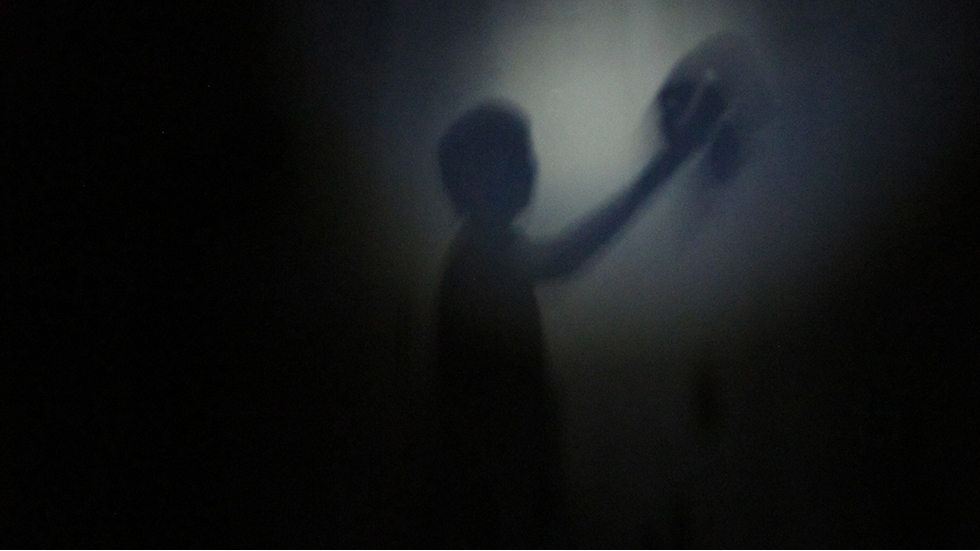

Rather than saying that you are a legend in Macao contemporary art, I see you as a courageous pioneer who had ignited a fire after another with energies of your life and let us see the most precious colours in the world. ‘Rainbow at midnight: the reality of night is darkness. I strive for radiance of seven colours.’ These lines that you wrote during the last days of life have been hovering in my heart. I also keep in mind an ambiguous image of your big hand as seen in Albert Chu’s video work Goodbye, Mr Kwok Woon (2003). I’ve heard that, when you were critically ill, you still kept on writing and drawing despite physical weakness. ‘Three treasures of the world: fresh flowers, women, ocean.’ Those shaky handwriting shows your enthusiasm for life: colours and vibrancies, lust and desires, as well as boundless and mysterious power… Joey Ho told me that she saw you feeling cold on the hospital bed and therefore took you a blanket handmade by her mother. Isn’t it sincere friendship that made such earnest exchange? Another time a foreigner asked for your autograph on your monograph. You were so weak on wheelchair but still tried very hard to sign and write his name properly. Doctor Filomena said you were so kind to the medical staff even though not feeling well. Your pursuit of life was not only for fun and pleasure, but to daringly and selflessly entrust yourself to others, and to use your life to affect others. I see such acts of passing on as radiance of rainbow colours.

‘These artists—or everyone, not necessarily artists—influence others in their own way quietly. Mr Kwok did not deliberately please anybody, nor did he pretend to be nice. He showed his best side at every moment. Even during his hard time or at the end of his life, he was still the same. I think a real artist or a real person should be like this. Sincerity is what we should have in our life. No matter you paint or whatever, this is the most important.’ – Joey Ho

‘Honoré de Balzac said, “What Napoleon achieved by the sword, I shall achieve by the pen.”‘

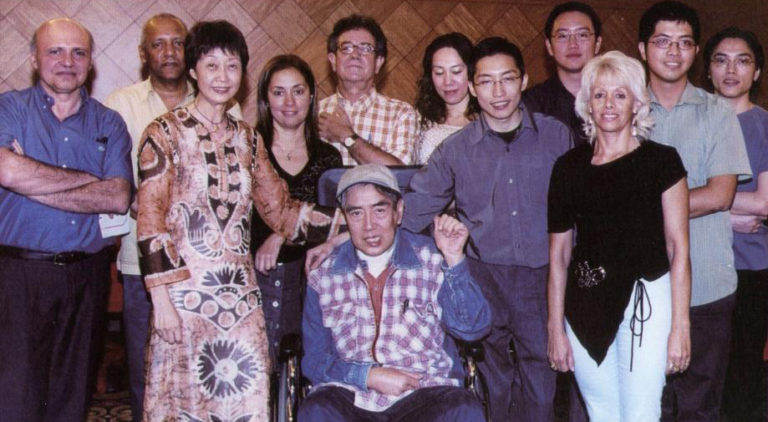

Talking about your intense relationship with friends in Macao, we cannot miss the two organizations: Círculos dos Amigos da Cultura de Macau (Núcleo de Pintura Contemporânea), and the Macao International Visual Arts Centre.

Ung Vai Meng, or ‘Meng Gor’ as you called him, told me an interesting fact that you, Carlos and Victor Marreiros, Mio Peng Fei, Un Chi Iam and him all spoke different languages: Portuguese, English, Putonghua mixed with Cantonese. You all seemed unable to understand each other, but still very communicative. You had a quarter of Dutch descent and close ties with Malaysia and Singapore; Mio and Un are from Shanghai; the Marreiros’ brothers are Macanese, and Ung is native-born. You all from different cultural backgrounds crossed your paths in such a small city, and were blended peculiarly well with diversity. Like knows like, despite your different styles of artmaking. Sometimes the group hung out for fun, sometimes you exhibited together in Macao or abroad. There is a photo in which you all struck different poses. It recounts intimate stories of a group of aspiring and dashing young and mid-career artists in the well-off 1980s. Each of you had your own talents, yet joined forces to set up an alternative scene.

Ung Vai Meng, or ‘Meng Gor’ as you called him, told me an interesting fact that you, Carlos and Victor Marreiros, Mio Peng Fei, Un Chi Iam and him all spoke different languages: Portuguese, English, Putonghua mixed with Cantonese. You all seemed unable to understand each other, but still very communicative. You had a quarter of Dutch descent and close ties with Malaysia and Singapore; Mio and Un are from Shanghai; the Marreiros’ brothers are Macanese, and Ung is native-born. You all from different cultural backgrounds crossed your paths in such a small city, and were blended peculiarly well with diversity. Like knows like, despite your different styles of artmaking. Sometimes the group hung out for fun, sometimes you exhibited together in Macao or abroad. There is a photo in which you all struck different poses. It recounts intimate stories of a group of aspiring and dashing young and mid-career artists in the well-off 1980s. Each of you had your own talents, yet joined forces to set up an alternative scene.

‘Kwok Woon is a very smart person. He could not speak English and relied on Joana to communicate with foreigners. But people can easily communicate with him. He’s not a rushed person, but very quick-witted. So he could understand things quickly. Sometimes we spoke to him in Portuguese and English that he did not understand, but with gestures he could understand right always.’ – Carlos Marreiros

Círculos dos Amigos da Cultura de Macau (Núcleo de Pintura Contemporânea) was founded in 1986, in response to the needs of the times. It is said that Macao art then was in general quite traditional, dominated by realistic and figurative forms. Six founding members of Círculos dos Amigos da Cultura de Macau staged the first exhibition Nine Artists (Portuguese Bookstore, 1987), together with José Catita, Antonio Conceição Junior and Ana Leandro. With non-realistic personal styles, the exhibition took Macao art scene by storm by presenting a fresh and visionary perspective.

‘Our group was like a big stone thrown into a pond,’ said Ung, ‘in which layers of ripple occurred, and then influences expanded.’ Since its inception, the group have presented joint and solo exhibitions in Macao, and also been invited to Hong Kong, Taiwan, Mainland China, Singapore, Malaysia, South Korea, Japan, Korea, India, and even Australia, Portugal, etc. I can imagine that you all had used your influences to bring Macao art to international arena. In addition to promoting Macao art locally and internationally, most importantly, the group established a platform for exchange of ideas and mutual support.

‘I used to be a junior compared to them, but they’d never looked down on me. We chatted as peers, very casually and very naturally. We made art together like brothers and sisters. During the process, we encouraged each other. In such a closed society like Macao at that time, recognition by others served as great motivation. We had a strong sense of belonging among six of us. You supported me, and I supported you too. We made it together. Our influences on each other’s style of presentation were limited, but we always supported each other.’ – Ung Vai Meng

Later in the 90s, the Visual Arts Institute located at Largo de Santo Agostinho (established in 1989, incorporated into the Macao Polytechnic Institute in 1993) was established, and arts activities organized by government or non-government groups were flourishing. The self-funded Macao International Visual Arts Centre was founded by you and Joana in 1997 and inherited the important role of Círculos dos Amigos da Cultura de Macau in promoting art. Joana once told me that she toiled and moiled with you for a few months, cleaning heavy dust and brushing the scratched floor. By the sweat of your brow, you two had turned the 4,000-square-feet 4-storey space from an abandoned fabric printing factory in Rua de Coelho do Amaral into a big window to and a platform for Macao art.

Yes, it was this Centre which offered opportunities of exhibition and even cultural exchanges to some fresh-graduate artists or art students such as Joey Ho, Tong Chong, Ng Fong Chao and James Chu who came back to volunteer later on. It is really impressive that solo and group exhibitions as well as seminars had been staged one after another at the Centre, not to mention reception of foreign artists, organization of Macao artists’ tour to abroad, etc. Your great effort grew out of your goodwill and enthusiasm for Macao art. Just like what you wrote in the catalogue celebrating the first anniversary of the Macao International Visual Arts Centre, ‘we just intend to create a settled space of freedom and creativity for myself and the like-minded.’ Thereby, the Centre was sustained not only by you and Joana. When people recognized your mission, they offered not only compliments but also their hands to join forces in graphic design, photography, logistics, etc. Even when you had passed away, the groups Associação Audio-Visual Cut and Comuna de Pedra moved into the space in Rua de Coelho do Amaral. Isn’t it another ripple effect indeed?

‘Only original things are the most viable.’

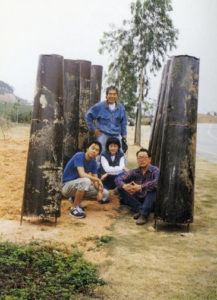

About your artistic practice, your friends are always keen on telling some interesting and memorable anecdotes. James Chu and Tong Jianying talked about the large iron cones used for grouting you picked up at Kun Iam Ecumenical Centre in the process of making your mural there. You re-welded and re-painted it according to their original cracks and textures, and created an installation titled Dialogue After the Cold War (1999). In order to document your work appropriately in a natural environment, they together with Joana, Tong Chong, joined you to move those eight 2-meter high big iron cones up to the green slope of Tai Tam Shan Park. This work, later presented with red and blue lights inside the cones facing each other respectively on a large platform of black and white checkerboard, won the First Prize in the installation category in the Fourth Macao Art Biennial.

In another work A Group of People Equipped with 120 gallons Idealism (1995), you used some large oil drums in green colour found in a construction site. In some big holes in a row originally on the drums, you pasted different hand-painted semi-abstract portraits. The two-and-a-half 50-gallon drums add up to 120 gallons, and the top with half-cut holes looks like a crown for those people with idealism. One more fascinating story, you were deeply attracted by the patchwork of a ragged canvas of a truck on the road in Zhuhai, then followed all the way to catch the truck and obtained the canvas by bartering a brand new one in the name of doing set design for a stage performance. Afterwards you cut the canvas into smaller pieces and painted them with some light and heavy strokes of bright colours according to its textile. You also mounted them on frames made of some burnt wood found in Linmao Tong after a fire. After then, 2 double-sided paintings Fortune (1, 2) (1997), and Caprice (1, 2) (1997), and the one-sided painting Fantastic Trail (1, 2) (1997) etc showing great intensity and adaptability were made.

The work mentioned above are all part of your Environmental Protection Series (1989-1999). ‘Environmental protection’ in general refers to recycling or transforming trash into something functional. One would refer to Marcel Duchamp’s Fountain (1917) for found objects, or to Robert Rauschenberg for assemblage art. Nevertheless, in the Environmental Protection Series, you used objects collected in everyday life. From them, you obtained inspiration with your acute sensitivity, and then created work basing on their natural traits, texture using your imagination and techniques. Hong Kong artist To Wun, who were once in the same exhibition with you, was especially impressed by your work made of fishing nets, floating wood, etc. You transcended materiality, transformed it into something abstract rather than merely creating collusive visual effects, and turned substances of a coastal city like Macao into original imageries. This not only demands an artist to go beyond imagination, but also to have careful observation and profound thinking in it.

The work mentioned above are all part of your Environmental Protection Series (1989-1999). ‘Environmental protection’ in general refers to recycling or transforming trash into something functional. One would refer to Marcel Duchamp’s Fountain (1917) for found objects, or to Robert Rauschenberg for assemblage art. Nevertheless, in the Environmental Protection Series, you used objects collected in everyday life. From them, you obtained inspiration with your acute sensitivity, and then created work basing on their natural traits, texture using your imagination and techniques. Hong Kong artist To Wun, who were once in the same exhibition with you, was especially impressed by your work made of fishing nets, floating wood, etc. You transcended materiality, transformed it into something abstract rather than merely creating collusive visual effects, and turned substances of a coastal city like Macao into original imageries. This not only demands an artist to go beyond imagination, but also to have careful observation and profound thinking in it.

‘These waste items are often seen in everyday life. People in general, or even every artist, do not have the ability to use them. However, when they came to Kwok’s hands, he used them casually, ordinarily, and very precisely. His work of installation at different times is very outstanding. […] Even pieces of trash wood and knots made of hemp ropes are expressive of his artistic perspective and philosophy. Artistic sense is crucial. In artmaking, expression of feeling is very important, and he is completely proficient in this. Works by others, I am afraid, are not quite there yet. His work is at its best, as he could get the right feeling. […] In order to manage these materials, first of all, one must have good eyes to discover which kind of them to use, and use them in a precise way.’ – Tong Jianying

Looking at your series of The Mysterious Orient (1992-2001) again, I deeply feel the power of your creative work that transcends the material world. Prints of ancient script, flying dragons, auspicious figures, etc are all stereotyped visual symbols in Chinese culture. Making a collage of these symbols in style of Western art can easily get attention with the notion of ‘East meets West.’ Joana told me that the image of dragon in each of the paintings in this series was collected in different places. In the pictures, there are some woodcut prints, Buddhist scriptures, and joss paper, etc which can be found but are often overlooked in Chinese folk religious culture. You always looked into details of folk crafts that are inconspicuous or even disdained as vulgarity, and respectfully incorporated them into your work of fine art. This is more than making a statement to restore their values. Your work comprises of careful composition of these folk images, and shows your reflection upon the myth of Chinese cultural roots. Injecting new life into traditional culture, I feel, is more original in artistic spirit than in a parochial sense.

‘He did his work very intuitively, not subject to spatial constraints. He used Western art media, and created enormous work. He’s not satisfied with writing only one or two lines or a poem. […] He did not have an ulterior motive. If you want to do sculpture, you will plan and work according to the size of your studio. But he often made work out of limited physical space, and eventually he did manage to do so. Unlike us who like to have complete control of our work, he just let the work to be made. […] He had never been calculating—or his kind of calculation is different from ours. He is a bit adventurous, a little bit different from other artists. I guess he did not think too much but would rather act most of the times. He inclined to Western style. Without scruple, his creative process is very personal. Nobody was checking him. And he did not have clear steps to work things out. This makes people often wonder how his work was made. Very impressive.’ – James Wong

In his preface to the exhibition Nine Artists, Mio Peng Fei proposed an artistic pursuit that artists ‘discover oneself through their inner eyes’ and ‘present their “real self” concealed beneath one’s appearance.’ This is an art manifesto of challenging the status quo and seeking novelty. In fact, before this exhibition, you and Mio had already been actively exploring and creating abstract paintings. I once heard a comment that abstract painting is a freestyle playing with the brush. This may only be partially true. There is a saying that one minute on stage stems from ten years of practice for a performer. Likewise, from your early work of watercolour plein air to later work which goes beyond physical appearance and figurative presentation, I understand how much practice and hard work you had made behind those significant work that might seem casual and freestyle.

That day I saw your retrospective exhibition Territories of Dreams at the Macao Museum of Art, and was totally immersed in your last few work of ink painting in the ‘Tao’ Series (2001-2002). I was stunned by the powerful way you swift between the real and the void space through the ink strokes, as well as your accomplishment of purifying your art. Through the strokes of lines and colours in abstract forms, I intuitively feel the pure spirituality. ‘Tao is vague and intangible. Yet, in the vague and void, there is image, there is substance. Within the profound intangible, there is essence; this essence is genuine. In it lies the great faith.’ quotes Lao Tzu from Chapter 21 of Tao Te Ching, in the painting Tao (6) (2002) which is on a soft fabric hung on the top and floating softly in the air. I was inspired: it takes a life’s time and energy to achieve such refined sophistication as one masters the art of transforming from physical world to an obscure abstract state and of drifting in-between the space connecting and complementing these two states. Indeed, how many artists can get the way (Tao) of breaking free from reality and attaining such spiritual transcendence of physical world?

‘To Live is good; to Dream is Even Better.’

James Wong once told me, ‘some people do art basing on his knowledge, skills, apprenticeship with a master, or the tools they have in hands, which are nothing about creativity itself. But the way Kwok Woon made his art wholly came from his personality. It’s all consistent.’ He also said that you are capable and courageous. This reminds me of a dangerous story I heard from Joana about making the mural in Kun Iam Ecumenical Centre. Time was limited and there was not even a long ladder on site. You made a platform using a wooden pane as bridge on which you lean yourself to paste the rice-paper prints on the dome and draw soft lines on the paper collage joining figures of different masters and Buddhas in the whole picture. Indeed, in preparation for the mural, you travelled all the way to Beijing and the Pilou Temple in Shijiazhuang for research. Referencing Chinese ancient lattice windows, you intelligently and innovatively put together thousands pieces of silkscreen prints on rice-paper on inner wall of the dome instead of painting on site. Your boldness was not only the virtue of a motor-racer or a wind-surfer, but also derived from your diligence and well-preparedness that let you complete your work confidently and consistently.

All of your friends say that you are an active and energetic person. To Wun from Hong Kong, who participated the Four Sides Art Exchange Exhibition (Hong Kong University of Science and Technology, 1999) with you, calls you ‘Peter Pan’. At the exhibition opening, you presented a piece of performance art work Frames by breaking through a pile of 50 wooden frames painted in red with a rowdy power-saw in the midst of flying sawdust. For sure, you were always totally devoted to your work. You often did the work yourself, so seriously that you even insisted to make frames for your work and colour them yourself. In order to mount your work tightly on a wooden frame, you worked with bare hands even if they were cut by the wires and bleeding. I also heard that for a while you had been using asphalt and glass fibre a lot in your work. The choking smell was so strong that even lots of plants in your rooftop studio cannot purify the air which might cause problems to your health…

‘He organized numerous exhibitions and art festivals at the Macao International Visual Arts Centre since its establishment. Nevertheless I used to be not very productive and often show the same piece of work in different places. He once explained to me that art practice shouldn’t be like this, and that I had to create more new works and show different work in each exhibition. […] After that, every time when I had an exhibition, I’d present a new piece of work. His influence on me is not only about the visuals of my work. Later on I have focused more on my own artistic practice; exhibition comes second. I am not making art for exhibitions, because I’m aware that I make art more often than having an exhibition. […] Later on, I had an opportunity of doing a solo exhibition. He told me that I had to go through a harvest time or at least a summative stage so as to move on. Otherwise, I would become muddle-headed in my creative practice. It’s him again who pushed me forward.’ – Tong Chong

Tong Jianying told me that you had never thought of yourself on the peak. During the last days of life battling cancer, you still worked very hard so as to attain a higher goal. In your last exhibition To Live is Good; to Dream is Even Better (Macao International Visual Arts Centre, 2002), a total of 30 works which you created in the past three years were presented. It witnessed your strong vitality. For an enthusiastic person like you, to live is the greatest blessing. From the pictures, I saw you on wheelchairs not able to speak but waving your hand to others arduously. A once strong and heavily built body withered, but your eyes were still flashing with strength. Life will end one day, but dreams can take us to somewhere splendid. Just like what Albert Chu said, you are like your work that have been widely collected and spread around the world. Through your art, you have ignited wonderful colours that brighten different corners of the world.

‘A few years ago I last dreamt of Kwok. It was amazing. I was in Portugal doing the biggest ever exhibition of Macao contemporary art at Museu do Oriente. The night before the exhibition opening, I dreamt of Kwok chatting and laughing. He was by and large saying that having dreams and reaching for it is the happiest thing. The next morning I told all other participating artists about this, just like a message from him.’ – James Chu

Meng Gor has not forgotten the 2 boxes of Stout that you owed him and his wife to celebrate his new born son more than 20 years ago. Carlos Marreiros still remembers the crawfishes he ate with you in Singapore. James Wong worries that there are so many people and cars in Macao now and you cannot drive fast as usual. Tong Jianying hopes that you continue your dream. Paula Pimenta also sees you keeping up your artmaking. To Wun remembers you are Chaozhouese too, and wants to do art with you again for fun. Doctor Filemena wants to have dinner with you again. Joey Ho recalls your happiness, and moments of making jokes and speaking loudly with lively body gestures. Albert Chu keeps in mind those drawings and notes you made before you passed away. James Chu imagines that you are still having exciting life in another world, and that he is still being spurred on by you. Tong Chong deeply misses you and your work that have influenced his manner of artmaking. And you are always in Joana’s mind.

What a pity that I have never met you when you were alive. Nevertheless, from the stories recounted by your friends, I feel like knowing you well. To make it straightforward, if I had chance, might I discuss with you about your masculine work from a feminist perspective, or the prospect of art in the shifting sociopolitical landscape now? I am sure you would welcome me as a new friend. Tong Jianying said that you often ‘left abundance of room and shared a mutual space’ when going around with different people. It is this mutual space that allows us to dream freely, isn’t it?

Sweet dreams!

wen yau

Special thanks to Albert Chu, James Chu, Joey Ho, Carlos Marreiros, Dra. Filomena Laia McGuire, Mio Pang Fei, Dra. Paula Pimenta, To Wun, Tong Chong, Tong Jianying, Ung Vai Meng and James Wong for their valuable time for interviews and letting me travel through time to meet Mr Kwok Woon. I would like to express my great gratitude to Joana Ling for her generous sharing with me. From her eyes, I can see Mr Kwok as a lively and vivid person. Also acknowledgements to staffs of Cultural Affairs Bureau and Macao Museum of Art for their research support.

Images courtesy of Ms Joana Ling, Cultural Affairs Bureau, Macao, and Macao Museum of Art

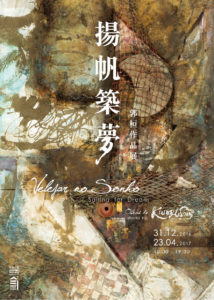

This article was originally published in the ‘Sailing for Dreams — Works by Kwok Woon’ exhibition catalogue; the exhibition took place in Navy Yard No.1, Macao, 31 December 2016 – 23 April 2017.

This article was originally published in the ‘Sailing for Dreams — Works by Kwok Woon’ exhibition catalogue; the exhibition took place in Navy Yard No.1, Macao, 31 December 2016 – 23 April 2017.

Editorial Note: The Cultural Affairs Bureau conducted a research on Kwok Woon’s art and his influences in Macao. wen yau, cross-media artist/researcher from Hong Kong, was commissioned to interview 13 artists and friends of Kwok so as to make a collage of the artists’ colourful life from multiple perspectives. In correspondence to Kwok’s lively character and creative manner, wen yau has written an essay in a letter form so as to present vividly the vibrant life of Kwok who was sailing for dreams.